The New Indian Express

18 August 2020

NCAT coordinator Suhas Chakma said torture adversely affects the entire criminal justice system and the no reform of criminal justice could be meaningful without addressing torture.

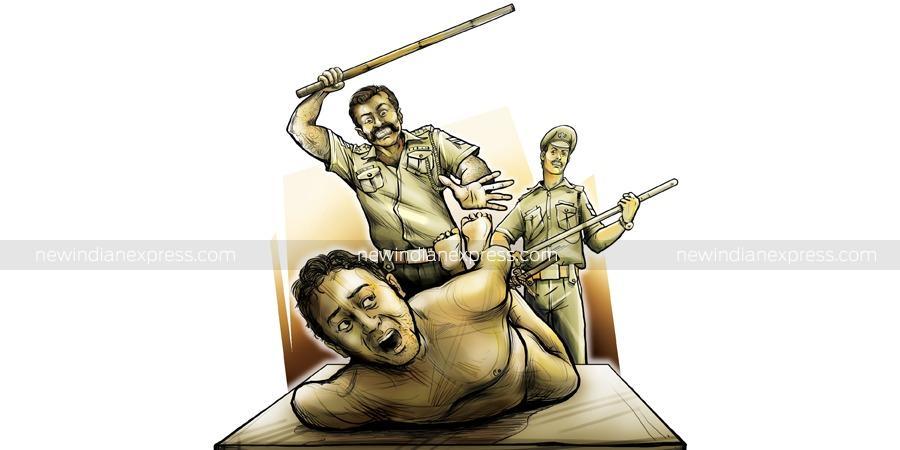

GUWAHATI: The National Campaign Against Torture (NCAT), in its submission — The indispensability of adding offences of torture in Indian Penal Code — lambasted the Committee for Reforms in Criminal Laws established by the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) for the exclusion of torture from its agenda on criminal law reforms.

“Union Home Minister Amit Shah, while addressing the 29th Foundation Day of the Bureau of Police Research and Development on 29 August 2019, stated that ‘the era of third-degree is gone’ and called for a nationwide discussion on amendments needed in the Indian Penal Code and the Criminal Procedure Code to address the same. However, the Committee for Reforms in Criminal Laws set up by the MHA has failed to include torture in its questionnaires for the First and Second Consultations on Substantive Criminal Law,” UNCAT coordinator Suhas Chakma said.

He said this self-censorship was a matter of grave concern as torture adversely affects the entire criminal justice system and the no reform of criminal justice could be meaningful without addressing torture.

The NCAT stated that the Constitution of India, the Indian Evidence Act, and the Criminal Procedure Code provided necessary safeguards against torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment by the public servants. However, the Indian Penal Code (IPC) does not adequately criminalise the offences of torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment when these constitutional and legal safeguards are violated by the public servants and therefore, acts of torture mostly go unpunished.

“The results are for all to see: The NHRC registered 35,554 cases of custodial deaths/rapes including 31,779 cases in judicial custody and 3,775 cases in police custody from 1994-1995 to 2018-2019,” the NCAT said.

It highlighted four shortcomings in the existing IPC provisions dealing with torture such as Sections 331 (punishment for hurt in custody) and 332 (punishment for grievous hurt in custody) read with Sections 319 (hurt) and Section 320 (grievous hurt). It stated that “grievous hurt” (Section 320) excludes many elements of “physical torture” which are routinely perpetrated; “mental torture” by the public servants is not defined under the IPC despite the Supreme Court in Arvinder Singh Bagga v. State of U.P. and others stating that torture “even consist of mental and psychological torture calculated to create fright to submit to the demands of the police”.

Hurt and grievous hurt do not include “cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment or punishment”; and the IPC provisions do not recognise torture being perpetrated “on the ground of religion, race, place of birth, residence, language, caste or community or any other ground whatsoever”.

“The Committee for Reforms in Criminal Laws has to decide whether India shall be a country governed by the rule of law penalising acts of torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment or a country permitting torture and other cruel and inhuman treatment of the persons by the public servants which the Supreme Court in Khatri & Ors v. State of Bihar, known as Bhagalpur Blinding case described as ‘insulting to the spirit of Constitution and human values as well as Article 21’ of the Constitution,” Chakma said.

The NCAT recommended to the Committee for Reforms in Criminal Laws to insert two new sub-sections “320(2): Torture and other cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment” and “331(2): Punishment for torture and other cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment” in the Indian Penal Code; and further insert a new sub-section 114-B in the India Evidence Act as recommended by the Law Commission of India in its 113th Report providing that for bodily injury to a person in custody, if there is evidence that the injury was caused during a period when that person was in the custody of the police, the court may presume that the injury was caused by the police officer having custody of that person during that period.

“The failure of the Committee for Reforms in criminal laws to recommend specific provisions for criminalisation of third-degree methods/torture would make the Committee itself redundant,” warned Chakma.